‘When people say “We must move with the times,” they really mean “You must do it my way.” And there are some who would say Ankh-Morpork is…a kind of vampire. It bites, and what it bites it turns into copies of itself. It sucks, too. It seems all our best go to Ankh-Morpork, where they live in squalor. You leave us dry.’

‘When people say “We must move with the times,” they really mean “You must do it my way.” And there are some who would say Ankh-Morpork is…a kind of vampire. It bites, and what it bites it turns into copies of itself. It sucks, too. It seems all our best go to Ankh-Morpork, where they live in squalor. You leave us dry.’

Ever since Twoflower stepped off a boat at Ankh-Morpork dock, becoming the Discworld’s first ever tourist at the beginning of The Colour of Magic, there has been a thread of modernity and progress running through each Discworld novel. I haven’t really touched on it so far, even though we have seen gonnes, submarines, political attempts to increase the racial diversity of the Ankh-Morpork, arcane computers, progressive monarchs and women not being bound by class or gender. To be quite honest, when I start thinking about what I *haven’t* had a chance to look at, I feel like doing a mass delete of every post, sticking the books up on eBay, taking my ball and going home.

Then I wise up.

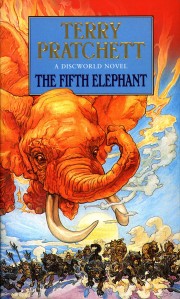

Thankfully modernity is shoved right at the reader in The Fifth Elephant, meaning it’s the perfect place to look at it here. Or as Pratchett himself says in the book: Time, in his experience, moved more like rocks…sliding, pressing, building up force underground and then, with one jerk that shakes the crockery, a whole field of turnips mysteriously slips sideways by six feet.

This ‘jerk’ is the building of the clacks, Discworldian semaphore that makes the world just that little bit closer. And a closer world means trade and trade means geopolitics and negotiating the shifting of resources between Uberwald and Ankh-Morpork. We are a long way from The Colour of Magic, where, in case you forgot, the highlight of the book was a fire in a pub. It was a hilarious fire, but that’s not really my point.

The Patrician needs fat and lots of it. Uberwald, which is in no way based upon Germany, has plenty of it, so Commander Vimes, the Duke of Ankh, is dispatched to attend the crowning of the new dwarf king and negotiate new trade routes. Coupled with this is the theft of the replica of the legendary dwarven artifact the Scone of Stone in Ankh-Morpork, Angua rekindling a “friendship” with an old wolf acquaintance, attempts by the various species in Uberwald to influence the dwarven succession and a hilarious strike at the Watch in Ankh-Morpork, which is left in the hopeless hands of Colon.

Lord knows how, given it is at least 10 years since I last saw it, but reading the political twists and turns of The Fifth Elephant, coupled with its machinations around natural resources, reminded me of Chinatown. Whether it actually is similar or not is debatable but one thing that it does have in common with it is just how out of his depth the protagonist is.

Vimes is hopeless at politics. He’s a copper, an incredibly good one granted but even he admits that diplomacy is not his strength. Take these thoughts about why he is even in Uberwald in the first place:

Vimes didn’t see the point. Gold…now that was important. People died for it. And iron – Ankh Morpork needed iron. Timber, too. Stone, even. Silver, now, was very…

Anyway, silver was useful, too, but fat was just…fat. It was like biscuits, or tea, or sugar. It was just something that turned up in the cupboard. There was not style to it, no romance. It was stuff in tubs.

He fails to realise ‘stuff in tubs’ is at the centre of what fuels an economy (note how Vimes refers to tea and sugar, two transformative resources in the ‘real’ world several centuries ago).

One does wonder why Vetinari’s terrier, as he has been nicknamed, was sent to Uberwald, given his tin ear for diplomacy. Perhaps Vetinari suspects *something* is afoot and Vimes’s, um, direct approach is the best way of thrashing out matters. And to an extent, he is right. By the end of the novel, Vimes has gotten rid of the more uncivilised players in Uberwald, negotiated a favourable trade tariff and flushed out a future threat, in the Vetinari-esque Lady Margolotta.

But it also shows just how quickly the Discworld was changing. When you think of Vimes, one thinks of David Cameron’s jibe at Tony Blair, when the ex-Labour leader was still Prime Minister: ‘You were the future once.’ Vimes used to be at the vanguard of a changing Ankh-Morpork, with his multi-racial police force and embracing of modern techniques like forensic science. Now he has been eclipsed by the clacks and trade tariffs.

But how modern is Ankh-Morpork? Vimes is taunted throughout by Wolfgang, the werewolf Angua’s unhinged brother and he who is trying to take advantage of dwarven instability, by being called ‘Civilised’. The city’s representative is someone who uses force rather liberally throughout the novel, before killing the heir of one of Uberwald’s most prestigious families by shooting a firework at him while he is in wolf form. Plus the now obligatory nagging doubts that Vetinari might be some legendary supervillain that is even conning the reader into believing he is one of the most fun characters of all time.

We learn Uberwald is progressive, to an extent. By the end of the novel the Machiavellian vampire Margolotta is drawn as no worse than Vetinari, as she helps redraw her country to benefit herself. As we learn when we read of her abstinence meeting towards the end of the book, there are things more seductive than blood:

Then you found that what you really wanted was power, and there were much politer ways of getting it. And then you realised that power was a bauble. Any thugs had power. The true prize was control. Lord Vetinari knew that. When heavy weights were balanced on the scales, the trick was to know where to place your thumb.

Now, you could try and argue that she is worse than Vetinari, but if you were to convince me, you probably should go into politics. There’s a general election on in a few weeks, apparently.

Then there’s the Low King of Uberwald, a progressive ruler and one looking above and beyond the underground of where he rules. He’s a background player for a lot of the novel, despite his import, but somehow it makes his revelation at the end more of a shock. He asks Cheery, the controversial dwarven Watchwoman who fully embraces her feminine side, for clothes advice. Is the dwarves’ ruler female? Trans? Or just fancies wearing a well-tailored dress whenever it takes his fancy? It’s not clear – the continued use of the ‘he’ pronoun suggests he is male but dwarven sexual identity is a complex issue, as Pratchett has established in previous books.

I feel it’s Cheery and Angua that underline that Ankh-Morpork is the more progressive society. Not by much, but enough. Cheery is a brilliant character and her struggle with her identity in Feet of Clay gave the book an intense emotional power and one that made the antagonist golem, also struggling with what he was, that more compelling a villain.

Here you see how shocking her lifestyle choices are in the eyes of other dwarves. It’s baffling but she is an outlier when it comes to her community. The approval of the Low King at end of the novel shows that things could change.

Angua is even more interesting. There are 16 Discworld novels after this and I would happily stick with it if I knew every one was about the Watch’s resident werewolf. She represents something different to the Discworld. Not a traditional werewolf like the rest of her family, some of whom are happy sticking to their traditional blood-crazed roles. Not a wolf, given her never quite explained relationship with Gavin, the wolf who brings her back to Uberwald. Not a human either, given her difficult dealings with Carrot and colleague. As Gaspode (GASPODE – the mangy talking mutt is back!) explains:

When she’s human shaped she’s just like a human. And what’s that got to do with anything? Humans don’t like werewolves. Wolves don’t like werewolves. People don’t like wolves that can think like people, an’ people don’t like people who can act like wolves. Which just shows you that people are the same everywhere.

But there is a place for both of them in the Watch, where they have no need to hide their true selves. And this is a place that is traditionally conservative, with its adherence to law, order and upholding the status quo. As ever with Discworld, things are complex, but what’s important is you are forced to think about these issues and tease out what is the best from all the available options. Vetinari may be Lex Luthor with a limp, but he’s also someone whose will can bend Ankh-Morpork into shape around it. Let’s just not mention that he is hardly leading a democracy, is he?

There are some neatly meta bits of plot here, which means I have to do the needful and draw attention to the fact that Wild Speculation may likely follow. There are two spectacular MacGuffins in the novel. The first is the Stone of Scone in Uberwald, which we eventually learn is a fake of a replica of a fake of a replica dating back decades after the original dwarves’ holy symbol first crumbled. Secondly there’s the eponymous Fifth Elephant itself. Pratchett has made a lot about the power of symbols and how it’s not what they *are* but what they represent that is so important. The Fifth Elephant, a pretty awesome pun in tribute to an amazing sci-fi film (and even better graphic novel) aside, serves no purpose but to attempt to explain why Uberwald is so resource rich.

Throughout the novel, we see how Ankh-Morpork versus Uberwald is the tale of ‘modernity versus the lore’. Vimes is repeatedly told he can’t win because he fails to understand the importance of myth. Things happen, but the lore endures:

‘There’ve been rebellions against kings before. Dwarfdom survives.The Crown continues. The lore abides. The Scone remains. There is…a sanity to come back to.’

As we see, that’s not true. Lore is defeated by modernity with the rather literal image of a mythical werewolf being killed by a flare from the clack. Something to chew upon (sorry). Pratchett has spent the best part of 25 books discussing the power of stories. Here he posits that there might be something more. Not necessarily better, but different and maybe more powerful. You could argue The Fifth Elephant is the first in his Industrial Revolution series (The Truth, which is discussed next week, is generally seen as the first). This is an area that will dominate the Discworld as it enters the Century of the Fruitbat.

As ever, a good sign of a Discworld novel is when I look at what I have typed and feel dejected that I have barely done it justice. There’s no mention again of Sybil Vimes, wonderful wonderful Sybil, Pratchett’s excellent grasp of long-term relationships and a content marriage. I (capital-L) LOVED Inigo, the slick diplomat-cum-assassin who was swiftly bumped off but I still hope escaped somehow. After their comedic brilliance in Carpe Jugulum, it was great to see the Igors back, although I assumed that Pratchett writing one who doesn’t have a speech impediment, out of sheer rebellion, must have meant they were a complete bugger to write.

The book heralds a change in what the Discworld is and where it is going. That’s its strength. It’s a novel that benefits from some thought after the book is long closed and neatly fits in with its publication time. We were all asking where we were heading as the years approached 2000. This book shows the Discworld has a decent idea. Next week’s book, the 25th (TWENTY FIFTH! Blimey), underlines it. See you next week for The Truth.

(Sam) Vimes didn’t negotiate a trade agreement, Sybil did, or at least, she did all the hard work.

Oh, and the Colon B-plot (or is it C or D?) is hilarious.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Interesting.

My reading of the Low King is that he is definitely female.

It is great to see Vimes out of his depth at times; in later books (post Thud!) he becomes something of a superman and his character and the books suffer as a result.

I can’t wait to see what you think of the utterly brilliant Night Watch; I’m enjoying this blog very much

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve read ahead so I now know about The Low King. It’s deftly handled in this book.

I completely agree. I don’t like the Vimes of the later books. He’s too pompous and superpowered.

The Night Watch was great – I felt it should have been the end of the Vimes arc. Full post in a few weeks after some absolute classics from Pratchett are looked at.

LikeLike

I thought the Low King twist was one of the two missteps. There’s nothing wrong with it in itself, but it comes right after using the same twist with another character. Having ONE ‘oh, wait, you mean…’ twist is funny and maybe meaningful, but having two looks like a stunt. [You hear me, Monstrous Regiment!?] – plus, the King is a more effective figure if he’s saying “I’m not female but I support you if you are”, rather than saying effectively “maybe I’m only supporting you being female because I am too”.

The other misstep…

…SLIGHT THOUGH OBVIOUS SPOILER…

…Vimes shouldn’t have beaten Wolfgang. Angua should. The novel is to some extent about how Vimes is at the end of his career, how he’s settling down with his wife and future child, and it ends with him finally taking a holiday (while Carrot basically takes his job back home). At the same time, the novel is also about Angua finally facing her past, and growing up into independence (as opposed to, up to now, merely being in hiding/on the run). Her plot all builds up to her laying her ghosts by killing the evil brother who killed their sister, and sticking a middle finger up to her mother at the same time. What SHOULD happen is that Vimes can’t beat Wolfgang, but Angua kills him (and using the flare, showing that she’s not just a werewolf but a civilised, tool-using werewolf, would be great). It caps both his and her plots.

Instead, all of that “I’m the only thing he’s afraid of” stuff, the army of wolves and so on, all ends up with a brief wrestling match that ends bafflingly (she’s winning, but then he leaves and she just yells instead of following him), and the father-figure of Vimes has to step in and save the day, which to my mind lets the coolness of Vimes override the thematic content of the book.

And yes, this should have closed Vimes’ story arc. From now on, Carrot should be in charge of the watch, and any future watch novels should be about Angua (they can’t be about Carrot, he and Vetinari are the only two characters who can’t be used as main characters) – or about a new recruit in a Watch run by Carrot and Angua. ‘Night Watch’ can then be set the day before Vimes retires for good and hands everything over to Carrot, and acts as his coda, closing his tale (though of course he could pop in now and then as a guest character).

Which is turn would set us up for the long, long long-promised showdown between Vetinari and Carrot, because those two may coexist in the short term but eventually you know Vetinari is going to do something Carrot can’t allow, and then the great dictator is overthrown by the universally-beloved king, who is democratically elected and then takes Vetinari out of prison to act as his advisor. Well, maybe not exactly like that, but Carrot’s got a Destiny that he’s been moving toward step-by-step until the last pages of The Fifth Elephant… and that then gets ignored for the late-cycle fixation, ‘All Vimes All The Time’ (he’s in 9 of the last 12 books, 7 of the last 8, and all of the last 5 – not including The Shepherd’s Crown, obviously).

[Kudos to Angua. Wrestles the villain while buck naked in public, AND is clearly (though not unambiguously) implied to have had sex with a dog in the past (well, wolf, not that that makes a difference), and still maintains her dignity in the eyes of the audience…]

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for a terrific review of one of my favourite Discworld books. On re-reading it recently, I found myself skipping past the ‘Colon left in charge of the Night Watch’ farcical side-show – funny the first time of reading, but it wears thin pretty quickly. In contrast, the political nuances of the book, and the development of relationships (Carrot and Angua, Vimes and Sybil) are all the richer for a second reading.

LikeLike

I think the Colon sub-plot nicely lightens a rather serious main plot. I fear without it, the novel might have suffered from the same ponderous tone that some of the later Watch book shared (Thud and Snuff, basically).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really good point that I missed somehow when I reviewed it: Vimes isn’t just out of place, he’s also out of time. This is important because Vimes really is a dinosaur (there’s a slightly awkward bit when people explain that racist and sexist harrasment is ok so long as Vimes does it…), and the plot in this books puts him in his proper place as a dinosaur, which works later than the later tendency to make him a perfect saint. Plus we get the irony of the future being pushed through by a man of the past, which also takes some of the sting out of the undertones of cultural imperialism – the future is, as it were, allowed to escape with relatively little taint, because the blame gets taken by the man of the past who brings it about (in much the same way that the first Old Stoneface took the blame for that revolution).

But one objection: well no, Uberwald clearly ISN’T inspired by Germany. Uberwald, as the name suggests, is inspired by Transylvania – traditionally Hungary, now Romania. The germanness of the names doesn’t take away from that, as there was a large ‘Saxon’ population of Transylvania. Indeed, we might suspect that Pratchett’s detente between vampires, werewolves and dwarves is a reference to, or inspired by, the Transylvanian ‘Union of Three Nations’ – the German-speaking ‘Saxons’, the Hungarian-speaking ‘native’ Transylvanian nobility, and the Szekely (a culturally-distinct Hungarian-speaking ethnicity of debated origin). The Union of Three Nations, like the three-way detente in Uberwald, completely ignored the local peasantry (human in Uberwald, Romanian in Transylvania).

The double-headed bat of the Uberwaldian ‘Unholy Empire’ is the double-headed eagle of Austria-Hungary and the Holy (Roman) Empire. Uberwaldian names like Bad Blintz, Glitz and Klotz suggest the -itz ending often found in Slavic areas conquered by Germans – i.e. in eastern europe and in the easternmost parts of Germany (most obviously Bistritz in Transylvania).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Cheers mate, I would like to email you but I can’t find any mail information.

Would you mind mailing me? 🙂

Great post by the way!

LikeLike

You should have mail!

LikeLike

Very good review! I’ve been rereading the Watch novels myself and wiring my reviews. 🙂 Next on my to read is the fifth elephant so I’m definitely going to muse over ur observations of the book. 🙂

LikeLike

Some more nitpicking!

> This is an area that will dominate the Discworld as it enters the Century of the Fruitbat.

Discworld was nearing the end of the Century of the Fruitbat. Hats off to the Century of the Anchovy! Quoting “The Truth”:

“Er. Well, then…you can say that I said it is a step in the right direction that will…er…be welcomed by all forward-thinking people and will drag the city kicking and screaming into the Century of the Fruitbat.”

“Yes, Dr. Dinwiddie. Er…the Century of the Fruitbat is nearly over, sir. Would you like the city to be dragged kicking and screaming out of the Century of the Fruitbat?”

LikeLike

That’s some top, top nitpicking 😃

LikeLike